Everybody by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins

directed by KT Turner

dramaturgy by Ariana Burns

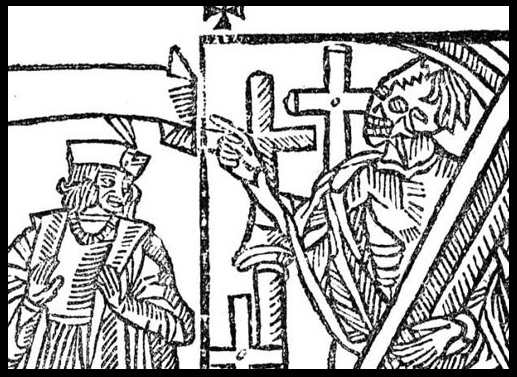

(Section of frontispiece from edition of Everyman published by John Skot c. 1530.)

Danse Macabre or Dance of Death is a medieval allegory about one’s own mortality that came about during a time when death was very much present. The allegory has been presented through a myriad of media including sculptures, murals, wood cuts, paintings, music and presentations (Hollar; Cohen, p 37). Murals were displayed on church walls and charnel houses where corporeal remains were stored and Gertsman wrote of a Parisian cemetery with a large mural surrounding its inner courtyard (p 1). Danse Macabres typically showed people in long processions with corpses in varying stages of decay (Hollar Collection).

The Danse Macabre probably claimed antecedents in pagan traditions. The practice of dancing in burial grounds did not stop after Christianity had spread into Europe (Cohen, p 37). Medieval cemeteries were not relegated to solely mourning and reflection. Gertsman found them to alive with a variety of activities:

…the medieval cemetery, not necessarily a mournful place, was a site of public picnics, promenades and celebrations—and therefore always busy and often given to worldly affairs. –Elina Gertsman, p 1.

As the church absorbed the graveyard dance, it transformed it into a moral pageantry (Cohen, p 37.) It was the fusion of these differing beliefs that would give rise to the Danse Macabre. Gertsman wrote that the Macabre imagery melded the ideas of death as communal and individual. Each person faced it on their own, in their families, and with the presence of mass burials at cemeteries. None could escape it. “The Nobleman and the Beggar of the danse macabre are both mortal in equal measure, and their indistinguishable remains will co-mingle at a charnel house….” (Gertsman, p31).

The most popular woodcuts of the Danse Macabre were created by Hans Holbien in about 1525 (Public Domain). His work has seen successive reprints over time.

Interestingly enough, when artists decided how to depict Death visually the most common representation was his own handiwork. Jean de Vauzèle, the Prior of Montrosier remarked on this in his preface to Holbien’s book:

"And yet we cannot discover any one thing more near the likeness of Death than the dead themselves, whence come these simulated effigies and images of Death's affairs, which imprint the memory of Death with more force than all the rhetorical descriptions of the orators ever could." (Wikipedia).

Death is often illustrated dynamically and full of more life than any of the other characters. As if being freed from the mortal coil, has given it more energy. Cohen wrote that he found the pain still within Death’s appearance:

“…the artists of the Dance of Death, by levity, satire and humour, render him a ‘jolly fellow’, a trusted friend. Nevertheless, anguish in the face of Death breaks when, as in our time, massacres and monstrous weapons of universal devastation are all too familiar, death as a dancer can no longer have any ‘reality’, even in fantasy.” (Cohen, p 38).

Along with the duality of Death being a communal and individual experience, the Danse Macabre brings it close and keeps it apart making it both friend and stranger to the people of the Middle Ages.

Cohen, John. “Death and the Danse Macabre.” History Today, vol. 32, no. 8, Aug. 1982, p. 35. EBSCOhost. Last accessed: Jan 21, 2021.

Gertsman, Elina. “Visual Space and the Practice of Viewing: The Dance of Death at Meslay-Le-Grenet.” Religion & the Arts, vol. 9, no. 1/2, Mar. 2005, pp. 1–37. EBSCOhost,

Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death (1523–5). The Public Domain Review. publicdomainreview.org/collection/hans-holbeins-dance-of-death-1523-5. Last Accessed: Jan 22, 2021.

University of Toronto’s Library Wenceslaus Hollar Collection. hollar.library.utoronto.ca/dancedeath.

https://www.uidaho.edu/class/theatre/productions-and-events/everybody