A Rumination about Stories from the Stoop, creating narratives from oral history interviews.

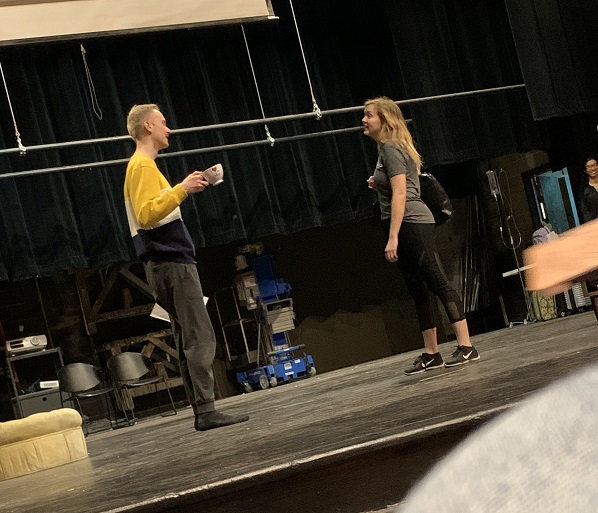

Latah County Historical Society (LCHS) had a socially-distanced gathering of storytellers at the McConnell Mansion a few weeks ago. It’s the closest I’ve been to a live theatrical performance since The Moors last March. Sandy Shephard read two pieces for me. One was new and the other was a story I’d prepared from a couple of years ago when I’d first participated in the event.

My favorite collection at LCHS is the Oral History Collection. A series of interviews conducted during the 1970s, they are a treasure of life in Latah County during the turn of the 20th century. The audio recordings reveal personal thoughts on big events like wars, epidemics, prohibition and small like having pet squirrels.

For these storytelling events, I pulled from the collection. One well documented person is Ione “Pinkie” Adair. She was interviewed multiple times and some of her journals are on file as well. Her family lived at McConnell Mansion and she worked in a variety of professions in her life including county assessor, teacher, and timber homesteader. One of her more renowned stories was her time as a cook for firefighters during the Great Fire of 1910 when 3 million acres burned in Idaho, Montana, and southern Canada. It was thought to be one of the largest forest fires in American history.

Reading from her journals and then taking the transcripts from her interviews, I created a monologue of her life homesteading and the Great Fire.

The stories told at this event are not expected to be factual. But a personal writing challenge for myself was to not fabricate anything while creating the monologue. In this case, I wanted to keep Pinkie’s authentic voice and word choices and her story.

(Left: Stories from the Stoop at McConnell Mansion.)

I did edit to sculpt the narrative, making it more of a subtractive than additive process.

As an aside–With regards to my readers, I don’t recall if the original reader listened to Pinkie’s interviews, but Sandy did to appreciate Pinkie’s mannerisms. Even so, Sandy wouldn’t mimic Pinkie’s speech for the entire reading. This storytelling is performative and Sandy would give words different emphasis vocally than Pinkie did conversing with an interviewer. Then it becomes a delicate balance between story and verisimilitude for us.

The original performance was done by my friend, Troy Sprenke. We talked about the campfire reading and how the text should be performed. Troy’s great with engaging the audience and pulling them in. She’ll ask questions of the attendees and get them thinking about what was happening to Pinkie.

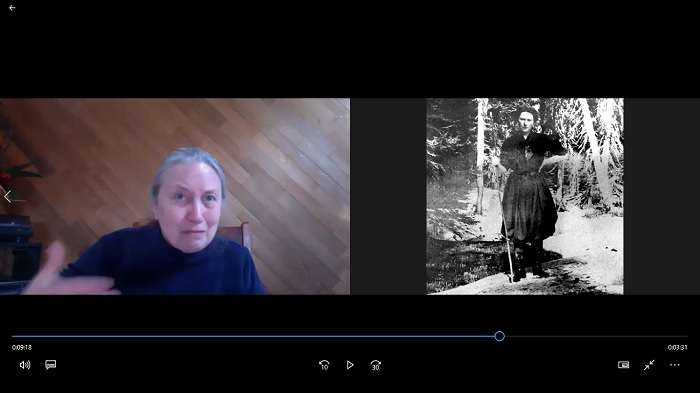

The piece was brought back this year as part of an online revue for the Kenworthy Performing Arts Centre and Sandy stepped into the role. This time it was a prerecorded Zoom performance which made it possible to insert a photograph of Pinkie alongside of Sandy. There were two rehearsals. We used this opportunity to tighten, cut some lines that were confusing the narrative, and make the overall story tauter and more suspenseful. Just generally improving the telling of it.

After the Kenworthy revue, it returned to the storytellers event and Sandy graciously agreed to read there. We didn’t rehearse as the piece was still fresh in her mind but she reviewed the script on her own.

I also compiled a new piece for LCHS by pulling up several interviews about the Bulgin religious revivals in the 1920s. These stories I wove together into a single narrative. This took more involvement/ interference on my part since I was drawing from a variety of narrators instead of a single person. It was a fun challenge to create the character they all embodied who would speak of what these revivals were like.

“I would think around 1920, give or take a year or so that Dr. Bulgin brought his revival to town. Lots of times people were carried away by the emotionalism of the crowd and everybody walking down, you know, to confess their sins. Some of them didn’t have any sins to confess! They were pretty good old people, you know! And they didn’t need to get so carried away.”

Elizabeth, “Walking the Sawdust Trail”

Sandy got the script and a couple days later we met on Zoom. We talked through the character of Elizabeth—Sandy named her. Between the two of us, we finished streamlining the story, editing bumpy text, etc. After the Zoom meeting, she worked on it some more and presented it with Pinkie’s story at the Mansion.

I love sharing stories from the oral histories if only to give the audiences a taste of what else is available for them to listen to online as told by the people who experienced it. And one really should go to the LCHS website and give the oral histories a listen.